Apparently Brendan’s mum wasn’t too keen on the line about the cigarette smoke. “My mum was saying – I don’t like that song, it makes me look like a bad mother”

Brendan talks to Culture Hub about the stories behind Sugar Island.

…

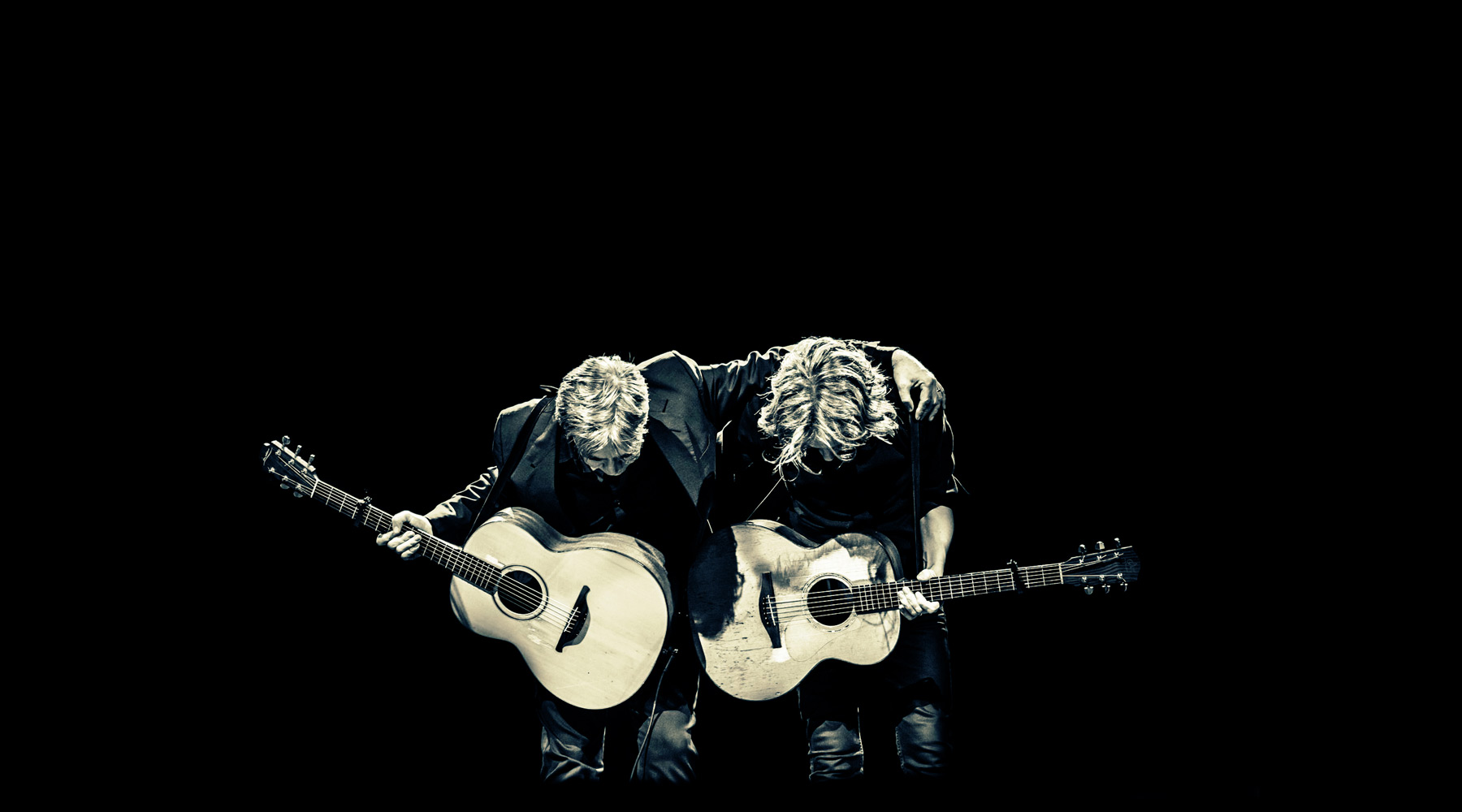

The 4 Of Us | Interview

By Cara Gibney

The 1970’s are a lifetime away, generations ago. A decade of its own very specific hue. Mungo Jerry summed up the summertime; there were flares and Kojak, and Creamola Foam.

Northern Ireland had its own specifics to add; we had The Troubles. The check points and the bomb scares and for many, unyielding pain.

Declan and Brendan Murphy of The 4 Of Us were growing up in Newry at the time, and while Wizard’s ‘See My Baby Jive’ was riding the waves on Radio 1, the Murphy boys were living at the top of the hill in Newry, with a birds eye view of the havoc being played on their city.

Since their 1989 hit ‘Mary’, The 4 Of Us have written, performed and toured their own material at home and abroad; winning awards and wooing fans. Innumerable singles later they are releasing their 10th album, Sugar Island in October, and this one is different. This one is looking back at the 70’s, at growing up with all of these things – normal and abnormal – as a backdrop.

“The album is primarily about me and Declan growing up” Brendan Murphy told me over coffee. He and brother Declan had driven up from Newry where they are still based, for a session on Radio Ulster with Ralph McLean. Explaining the idea behind the album, he was pointing out that it isn’t written about ‘The Troubles,’ it is about their life and times, their own history, of which the conflict in Northern Ireland was a huge part – but not the only part. “The troubles were just a backdrop,” he continued. “That makes it interesting. Otherwise it’s more an exercise in nostalgia, and there’s less reason to do it. Ultimately it’s an interesting story that I haven’t really heard in a song before.”

The Murphy brother’s story is pretty typical of a lot of people at the time. The conflict had always been there, it was normal, there was nothing outstanding about it. It was only when The 4 Of Us started touring that he realised that The troubles/the Northern Irish conflict/the guerrilla war he had grown up with, was indeed a big deal to people outside Ireland. “When the band first took off we were touring all round Europe. It used to really bug me because everybody would be questioning us about The Troubles in the north. In England, Spain or Sweden, we’d go into radio stations and they would say “Oh you’re from the north,” and they’d have this pained expression. You’d get really defensive about it because for me everything was fine, it was no problem. Then I came home and for the first time I realised hey, this isn’t that normal at all.”

Sugar Island is dotted with songs illustrating this very point. Tracks like ‘Bird’s Eye View’ talking about living on that hill as children, watching the blue lights and red flashes in the city below as another night of violence unfolded. “I’ve heard a lot of songs about the Troubles but what I haven’t heard is what my experience was, which was people trying to live normal lives with the Troubles in the background.”

Brendan is well aware though that this reality or ‘normality,’ was so much starker for others caught up in the turmoil, and that it wasn’t a task to take lightly. “We were just kids … I knew people who had tragedy, but I didn’t have it directly” he was keen to point out. “I knew that if I did write about it, that it’s a dangerous area to get into. It would put me off nearly listening to it if someone said to me here’s a song about The Troubles. I’d be thinking “Ah Jaisus, here we go again”.

However if the brothers were to write this album, then ‘The Troubles’ needed to be addressed, so they did this through the eyes of the children that they were, just getting on with their lives. “There is a song called ‘Going South’ he continued by way of illustration. It’s the story of Murphy family summer holidays in the south of Ireland, which ultimately ended up in long queues at the border checkpoint. “You couldn’t wait to get to the beach or get to Butlins or wherever. But there’s the checkpoint, and there’s loads of you [in the car]. It was that annoyance of taking forever to get just across the border. Belfast was the same; it would take you forever to get to the other side of the city because of bomb scares or whatever. To us as kids it was just the annoyance of it.”

“Counting every car behind us in the line

Waiting at the checkpoint marking time

Rolling down the window so I don’t have to share

The cigarette smoke hanging in the air”

Apparently Brendan’s mum wasn’t too keen on the line about the cigarette smoke. “My mum was saying I don’t like that song, it makes me look like a bad mother” Brendan laughed. “I just told her that everybody was doing it back then. In a funny way for me a line like that exemplifies the idea of the 70’s because it’s more of a reference point … people can relate to it.”

There is another angle to all this that deserves to be noted and those of us of a certain age will relate to it well – the challenge our parents had bringing their children up in these dark times. “For me on the album, I don’t say it, but the heroes are my mum and dad” Brendan told me. “They knew what was going on, and they were trying to make us feel like nothing was going on. That it was all normal … they couldn’t really shield us from it – it was on our doorstep. But they really did a damn good job in our case of making us feel like we had a normal childhood. We just did what other kids did.”

Not all the tracks on the album hark back to the conflict. Title track ‘Sugar Island’ for example is a tale of throwing away that love, the one that will haunt you for years after the event. “It’s not real” Brendan admitted. “Anybody I said goodbye to on Sugar Island, I’m glad I said goodbye to” he added with a laugh. “I know people who have let the one go, they’ve made that mistake, but luckily I haven’t”.

Continuing on the 70’s theme, the track ‘1973’ gifts us with vignettes of characters from the era. It stems from a conversation Brendan had with his father. “I asked my dad about what period of his life he had the most fun in, and he told me it was when the kids were young.” This inspired Brendan to write the song. “I started off [writing the song] with daddy in mind, and then I started writing about a different character completely.” With a sense more of the changes that age brings to us, the song is gentle, wistful, is riddled with references to ’73, and rings true with anyone who has parents of that age.

In its final track the album has moved on. In this song the band see what was happening through grown up eyes. “At the end of the album there’s a song called ‘Hometown On The Border‘, Brendan explained. “It’s the only song that speaks about how what I thought was ordinary, actually wasn’t really ordinary at all. In every other song I’m in the mind of a kid, it’s all happening in the present tense. But in the last song it’s me [as an adult] looking back. We put that song on the end just to explain the context. [The point being] that it shouldn’t have been ordinary. Without putting that in, the record didn’t seem complete.”

Around 50 songs were written for the album, which Brendan pointed out is the most narrative collection of songs they have released in their two decades as a band. “As a lyricist I wanted it to be more in terms of short stories” he explained. Because his background is more “rock and roll with not much story telling going on,” this was somewhat of a departure for the band.

Nashville is one reason for this shift in direction. A few years ago Brendan started visiting Nashville to work on his song writing. While there he met song writer Sharon Vaughn who subsequently, so many years later, travelled over to Ireland several times to co-write Sugar Island with Brendan and Declan. Her angle on the songs and the writing of the songs was incisive. “We knew that if we worked with someone who was a stickler for detail, and who was outside our experience that it would be good for us” Brendan told me. “Sometimes I would be writing something and she would say “I don’t understand that.” This helped the whole song writing process because it clarified what wasn’t clear; it helped with the things that were only really understood by people who had been there.

“She’s used to working with acoustic guitars” Brendan went on to explain of the experienced hand who was so influential on the album. “Her background is country – old country. She has written for Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings. She wrote one of Willie’s biggest songs, ‘My Heroes Have Always Been Cowboys’ so she was a great sounding board.”

Other collaborators on the album include percussionist Peter McKinney and multi-instrumentalist Enda Walsh, each adding their own specific touch to the sound. For example, the songs of Sugar Island generally don’t involve drums. This was as much to give the record its own unique sound as it was for practical touring reasons, as Brendan explained. “Because we are touring this primarily as a two piece with Declan playing the stomp and rhythm guitar, we thought let’s have it sound rhythmic without having a drummer. If you listen to the record you’ll be hard pressed even to spot a cymbal. We knew early on that if we went down that route we’d end up sounding different from other records.”

THE 4 OF US | Official Website

2 brothers from Ireland, Brendan and Declan Murphy with 2 acoustic guitars telling stories in song